These days we understand how it works.

We realise that we’re all just individual nodes of productivity. That we’re paid for what we’re worth – and that’s not much.

We accept that the only worthwhile fight is the one amongst ourselves as we scrabble and scrap in a fiercely competitive jobs market. We’re taught by the media to avoid shirking, to tighten our belts – to happily work longer, harder and for less reward.

If an employer makes unreasonable demands – well, that’s tough. There’s nothing we can do, so we suck it up.

The Midnight Terror

But in the south Wales valleys of the 1820s, they did things differently. If they felt they were being unfairly treated or that a reasonable request was being ignored, they would send a warning letter to their boss.

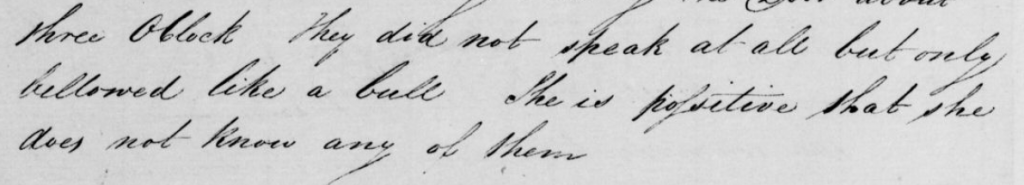

If this was ignored, a group of around 10 to 20 workers would gather, faces blackened – some wearing animal skins, some dressed in women’s petticoats, some blowing horns and bellowing like cattle. Some armed with axes, clubs and chains.

And they would march to the home of the employer for something which would become known as the ‘midnight terror’.

They would force their way into the property and start to destroy the owner’s possessions. Sometimes the target himself would be roughed up, but they were mostly left alone.

The gang wouldn’t steal anything, they wouldn’t touch any of the food in the house, but the furniture would be smashed, the windows broken and the owner’s clothes burnt in the fireplace.

And once the gang were done – they would disappear back off into the night.

On the front door, the victim would find a bull’s head had been daubed in red paint – the calling sign of the Tarw Scotch (the Scotch Bull).

Birth of the Bull

Birth of the Bull

This was a mysterious group which emerged in the south Wales valleys during the early C19th. It was made up of coal and iron workers who formed themselves into a secretive collective.

It operated over an industrial region known as the ‘Black Domain’; it extended from Rhymney to Abergavenny and from Llangynyidr to Caerphilly.

The aim of the group was to encourage unity amongst workers and to fight against the greed and exploitation of the works’ owners. Their motto was: “Y gelyn pob dychryndod” (The enemy of all fear).

They would target anyone they viewed as supporting the owners: strike-breaking ‘blacklegs’, corrupt landlords, officious bailiffs and the hated owners of truck shops – instead of cash, workers would receive tokens that could only be spent at a company-owned store.

For 25 years the Scotch Cattle acted as a brooding and ghost-like presence in the south Wales valleys – an all-seeing eye which kept watch over workers; emerging from the shadows like a cow-themed superhero to right any wrongs.

It was a group formed out of desperation. Working life back then, much like now, was a mix of poverty, fear and paranoia. Privately owned mines and ironworks would constantly hire and fire workers as demand waxed and waned.

They could do this as large numbers of migrants from England and Ireland were starting to move into the region, making the local workers an increasingly disposable commodity

It meant that one of the few tools they had to protect their interests against the owners, the threat of a strike, was becoming less effective as they could be so easily sacked and replaced.

It created a brutal climate in which workers found themselves powerless. The only way they could start to fight back was by grouping together; to start finding ways in which they could challenge a system so slanted against them.

It was in this atmosphere that the Scotch Cattle emerged.

Why Scotch Cattle?

Why Scotch Cattle?

Nobody knows where the group’s weird name came from but there are a number of different theories:

- Named after railway ‘scotches’ – wedges used to prevent rail wagons from moving – in the same way, Scotch Cattle could bring works to a halt.

- A reference to the Highland breeds of cattle that many of the rich owners kept during this period as a status symbol.

- Miners wore leather hides/jackets to work; combined with their soot-blackened faces, it gave them the appearance of bulls.

- It’s from the term ‘to scotch’, meaning to injure or do harm to somebody.

But it’s most likely linked to the menacing size and appearance of Highland breeds of cattle. The group used a bulls’ head as its insignia – it was drawn on the Scotch Cattle’s warning notices and daubed on the doors of homes they ransacked.

The cattle theme extended to the group’s structure with different pits/villages having their own ‘herd’ and the leader being known as the ‘bull’.

The secretive nature of Scotch Cattle makes it hard to estimate how many members it had or exactly how it was organised. One letter sent by the group boasts of them having 9,000 ‘faithful children’, but it’s likely that there was a fairly small core group whose activities attracted wider support.

One of the ways we do know they communicated was by holding regular hillside meetings in isolated locations such as Llanhilleth. These were held at night with hundreds gathering to share information and debate tactics/targets.

Guards would prowl the area while the meeting was held, firing off gunshots to ward off unwanted guests.

Mad Cow?

The newspaper reports at the time tend to portray the Scotch Cattle as an uncontrollable mob; as angry and irate workers who were unleashing their pent-up fury. But the court cases really don’t support this.

They seem to have operated in a remarkably well-disciplined and controlled manner. They had their own internal rules and limits on what was and wasn’t acceptable and the focus of their violence was on possessions rather than people.

The court cases provide examples of Scotch Cattle raiders being disciplined by other group members for overstepping the mark – for being too violent or causing damage to property not linked to the owner.

Their violence wasn’t an emotional outburst – it was a means to an end. They wanted the owners and the establishment to fear them – that was the point.

But they also understood that the bark could be much more powerful than the bite. It’s why they turned their ‘midnight terror’ sessions into such loud and theatrical displays.

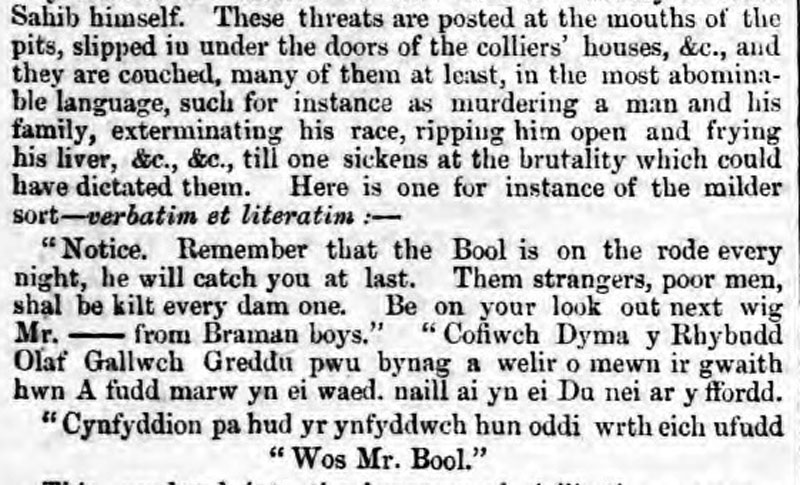

Despite their reputation, the group’s most effective weapon was always its use of words. It was the warning notices and letters they issued which would resolve the majority of disputes.

These would be written in red ink (sometimes animal blood) and pinned to the door of a target or posted to a workplace noticeboard. Here’s an example of a Scotch Cattle notice posted up at Clydach Ironworks in 1832 which targeted strike-breaking workers:

To all colliers, traitors, turncoats and others.

We hereby warn you the second and last time.

We are determined to draw the hearts out of all the men above named,

And fix two of the hearts upon the horns of the Bull;

So that everyone may see what is the fate of every traitor – and we know them all.

So we testify with our blood.

When these kinds of blood-curdling warnings were ignored, however, the Scotch Cattle was prepared to bite. And one of their favoured methods was industrial sabotage. Coal trains would be smashed, sections of railway ripped up and canal barges sunk.

During one dispute at Llanhilleth in 1822 the Scotch Cattle built up a bonfire made from 30 coal wagons with local newspapers reporting the fire still burning four days later.

But despite these public shows of defiance, prosecutions against Scotch Cattle members were rare. When they did get prosecuted, the cases would often collapse through a lack of evidence.

The Scotch Cattle would use ‘herds’ from neighbouring areas to carry out any criminal activity so as to reduce the chances of anyone being identified. The authorities, in their desperation, would also often resort to exaggerating flimsy evidence and relying on dubious witnesses.

In 1832 the Home Office put up a reward of £100, a major amount in those days, for anyone who would inform on the Scotch Cattle. Individuals, such as the owner of the Blaina ironworks, also issued their own financial rewards to encourage informants.

Out to Grass

It was only through a clumsy mistake that the authorities finally got a breakthrough. On October 28, 1834 a gang of Scotch Cattle went to visit the home of a strikebreaker called Thomas Thomas in Bedwellty.

As they tried to enter his home, his wife Joan Thomas, levered the door shut with a broom. As the men struggled to open the door, a shot was fired and the woman was hit above the elbow. She died from the wound two days later.

It’s not clear whether the shot was fired by a misfiring weapon or shot at the property as a warning. What is clear, however, is that a gang member called Edward Morgan didn’t fire it.

But he was the 32-year-old collier who would be convicted for the death. He was hung in Monmouth Prison the following year; a death hailed as a major victory for the authorities in their long-running battle with the Scotch Cattle.

In truth, it seems to have had little impact. The group continued to operate up into the 1840s, with their activities gradually fading as the Chartist and trade union movements began to offer an alternative form of protest and protection.

But the Scotch Cattle had planted a seed. It had demonstrated how a system based on exploiting those below could be challenged by the people at the bottom – through collective action and a refusal to live in fear.

Pingback: How scotchcamel.com got its name – ScotchCamel.com